I keep having the same conversation with different people.

It usually starts with “is now a bad time to buy servers?” and ends with someone quietly realising that the spreadsheet they trusted six months ago is now complete fiction. Not optimistic fiction either. Fantasy.

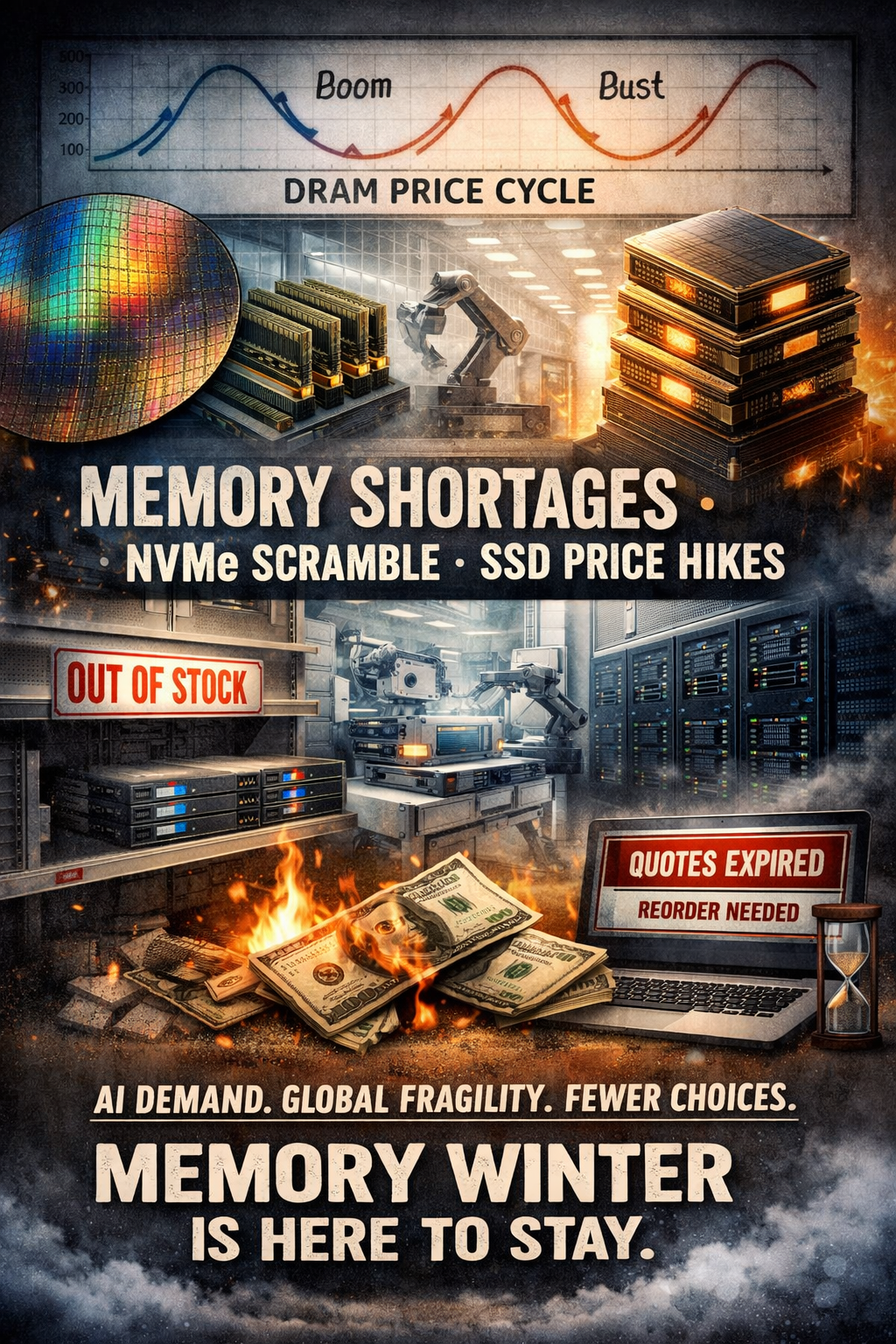

This isn’t just DRAM being awkward again. It’s not a temporary wobble. And it’s not confined to one tidy corner of the market. It’s hitting RAM, NVMe, SSDs, servers, PCs, storage arrays, and pretty much anything that depends on silicon turning up on time at a sensible price.

The important bit is why this is happening, because once you understand that, the behaviour of the market stops being mysterious and starts being depressingly logical.

Memory is a commodity, but supply moves at glacial speed

DRAM and NAND behave like commodities. Prices are set by supply and demand, not by what parts “should” cost or how annoying the increase feels.

The catch is that supply is brutally inflexible.

A modern memory fab costs tens of billions and takes years to become useful. You can’t spin it up quickly when demand spikes. You can’t slow it down cheaply when demand drops. And you can’t painlessly switch it between different memory types without consequences.

That means the market is always late.

Late to cut supply. Late to add it back.

In calmer times, that creates the familiar boom and bust cycle. Right now, it’s colliding with something much bigger.

AI doesn’t just increase demand, it warps it

AI infrastructure doesn’t politely sip memory. It inhales it.

HBM gets the headlines, but that’s only part of the picture. AI datacentres also consume vast amounts of conventional server DRAM and an ever-growing pile of fast, durable NAND. Training, inference, checkpointing, scratch space, data pipelines. All of it eats memory and storage at scale.

That creates a very simple incentive problem for manufacturers.

If you’re a memory vendor and capacity is tight, do you use your best wafers to make low-margin consumer DDR and cheap SSD flash, or do you turn them into server DRAM, enterprise NVMe, and HBM that hyperscalers will happily prepay for years in advance?

There isn’t really a decision to make.

This isn’t “running out”, it’s being redirected

One of the most common misunderstandings is that memory is simply running out.

It isn’t.

What’s actually happening is that capacity is being redirected.

The bulk of global DRAM production sits with a very small number of players: Samsung Electronics, SK hynix and Micron Technology. When they decide to prioritise server DRAM and AI-adjacent products, that capacity has to come from somewhere.

It comes from consumer DIMMs.

From mobile memory.

From older DDR standards.

From commodity NAND.

That’s why prices rise even when PC or phone demand is flat. Supply isn’t shrinking by accident. It’s being squeezed on purpose because it’s no longer strategic.

NAND, NVMe and SSDs are dragged along for the ride

This is the bit that often gets missed.

This is not just a RAM problem.

NAND follows exactly the same logic. The same fabs, the same vendors, the same incentives. When capacity tightens, enterprise SSDs get priority because the margins are better and the contracts are longer. Consumer NVMe drives get whatever is left.

The symptoms are familiar if you’re paying attention.

Capacities stall.

Price per terabyte creeps upward.

Popular models quietly disappear or get replaced with more expensive ones.

Storage doesn’t escape this cycle. It’s welded to it.

Fragility makes everything worse

We’ve seen this system crack before.

Flooding. Earthquakes. Power failures. Political shocks. When manufacturing is geographically concentrated, physical disruption doesn’t cause local pain. It causes global chaos. Entire supply chains wobble because one region has a bad month.

That fragility never went away. It was just hidden when prices were low and capacity was abundant. Now there’s no buffer left. Any disruption feeds straight into availability and pricing.

Why this cycle feels worse than the old ones

In the past, high prices eventually triggered overinvestment. New fabs came online, supply overshot, prices collapsed, and the cycle reset.

This time the timelines don’t line up.

New fabs are being built, but they won’t matter until 2027 or 2028. Much of their output is already spoken for before the first wafer leaves the cleanroom. Even when supply grows, it doesn’t flow evenly back into the market.

AI has become a permanent, high-margin sink for both memory and storage. Hyperscalers lock in allocation years ahead. Everyone else competes for what’s left.

Why this hits everything

This isn’t a server-only problem. Or a PC problem. Or a storage problem.

Memory and flash sit underneath almost all modern computing. Servers feel the pain first because that’s where demand is strongest, but the shockwaves propagate outward.

Storage arrays.

NVMe drives.

Laptops.

Desktops.

Phones.

Routers.

Embedded systems.

Industrial kit.

Hobbyist hardware.

When the foundation shifts, everything built on top of it moves.

What this means in practice

OEMs respond in predictable ways. Prices go up. Quotes expire faster. Lead times stretch. Configurations get weird. Parts quietly disappear.

Servers jump by double digits. PCs creep upward. Storage-heavy systems get hit hardest.

From the outside it looks chaotic. From the inside, it’s entirely rational.

What the data actually shows

This isn’t just vibes and anecdotes. You can see the shift clearly in public pricing data.

Looking at PCPartPicker’s UK price tracking over the last 18 months, DDR4 and DDR5 pricing tells the same story across almost every capacity and speed tier. Long periods of flat or gently declining prices are followed by sharp step changes upward, not gradual rises. Once prices jump, they don’t really come back down. They just plateau at a higher baseline.

Lower capacity kits move first, then higher density parts follow. DDR4, which should be in terminal decline and getting cheaper, instead rises alongside DDR5. That’s the tell. This isn’t demand from gamers or PC builders. It’s supply being squeezed upstream.

By late 2025, higher capacity DDR5 kits in particular show sustained upward movement with far wider price dispersion, meaning fewer cheap options and more variability based on availability. That’s classic allocation pressure leaking into retail pricing, not normal consumer demand behaviour.

In other words, the consumer market isn’t driving this. It’s inheriting it.

You can see the trend clearly across multiple kit sizes and speeds in the PCPartPicker memory price trend charts covering the last 18 months

TThe uncomfortable conclusion

This isn’t a temporary spike that conveniently unwinds next quarter.

What the pricing data shows is a reset, not a blip. Memory pricing has stepped up to a new baseline and stayed there. The dips are shallower, the recoveries are faster, and once prices move up, they don’t really come back down. They just stabilise higher.

AI is now the primary customer, and everything else follows behind it. DRAM moved first, NAND followed, and NVMe and SSDs have been dragged along for the ride. PCs, phones, servers, storage and embedded systems are all downstream of that shift, whether demand in those markets is strong or not.

The volatility hasn’t gone away. It’s just been turned into a tool. Allocation, not price competition, now decides who gets parts.

If you’re buying hardware, the lesson is blunt. Budgets based on last year’s pricing are already wrong. Waiting rarely helps. The charts show that hoping for a meaningful pullback in a rising market is usually more expensive than buying earlier and accepting the current pain.

Memory winter isn’t ending.

It’s being industrialised.

Key takeaways

Memory and storage pricing has structurally reset

The long, gentle downward trend is gone. Prices now move in steps and settle higher.

AI reshapes the entire market

Capacity is pulled toward high-margin server DRAM, HBM and enterprise flash first.

Supply isn’t disappearing, it’s being redirected

Consumer and legacy parts lose out even when end-user demand is weak.

Everything is affected

Servers first, then storage, then PCs, laptops, phones and embedded systems.

New fabs won’t bring fast relief

Additional supply arrives in years, not quarters, and much of it is pre-allocated.

Waiting is usually a losing move

Retail pricing data shows stalls and plateaus, not meaningful reversals.

Hope isn’t a strategy anymore

Planning around volatility is now mandatory, not optional.

References

Memory Pricing information – https://uk.pcpartpicker.com/trends/price/memory

Industry News – https://www.theregister.com/

Leave a Reply